Gastric Dilatation Volvulus (or Bloat) in Dogs

Gastric dilatation volvulus (GDV), often referred to as “bloat”, “twisted stomach” or “gastric torsion,” is a serious condition caused by abnormal dilation and twisting of the stomach. The condition is initiated by an abnormal buildup of swallowed air, fluid, food, or foam in the stomach. Bloat can occur with or without “volvulus” (twisting), occurring between the esophagus and the upper intestine.

- When the stomach twists completely, gastric emptying is completely obstructed, and the dog cannot obtain relief of air or stomach contents by belching or vomiting. In fact, a hallmark symptom of torsion is non-productive retching or vomiting.

- The bloated stomach obstructs the return of blood from the veins in the abdomen leading to low blood pressure, obstructive shock, and associated complications. The dog also may seem short of breath due to pain, and the physical compression of the chest and diaphragm caused by the expanding stomach.

- The combination of bloating and torsion immediately reduces blood supply to the stomach (gastric ischemia), and this can lead to necrosis (death) of the stomach wall.

- Shock and lack of blood supply to organs in the abdomen break down the integrity of the gastrointestinal tract lining and permit toxins and bacteria to enter the bloodstream.

- The spleen can be damaged or begin to bleed because it is attached to the stomach by a membrane, and it becomes twisted and rotated abnormally as the stomach turns.

- Heart function is compromised due to lack of venous blood return. Irregular heart rhythms often develop such as ventricular tachycardia.

- Shock and death follow if the condition is left untreated or if treatment is initiated too late in this devastating sequence.

Risk Factors for Gastric Dilatation Volvulus (GDV)

There have been many risk factors identified for GDV in dogs which may include, but not be limited to, the following:

- Dogs with deep chests and large breed dogs between the ages of two and ten years are at risk, although it is more common in older dogs. Breeds most affected include the Great Dane, Standard Poodle, Saint Bernard, Gordon Setter, Irish Setter, Doberman Pinscher, Old English Sheepdog, Weimaraner, and the Basset Hound.

- Eating or drinking quickly

- Stress from boarding, traveling, or a vet visit

- Fearful, nervous, or aggressive temperament

- Eating or drinking before or after exercise

- Eating a single large meal each day

- Consumption of large amounts of food or water

- Eating from a raised food bowl

- Eating only dry food

- For more information on risk factors, go to Is Your Dog at Risk for Bloat?

Signs of Bloat in Dogs

- Drooling

- Nausea

- Restlessness

- Abdominal distension

- Abdominal pain

- Non-productive retching

- Weakness

- Collapse

Diagnosis of Gastric Dilatation Volvulus (GDV)

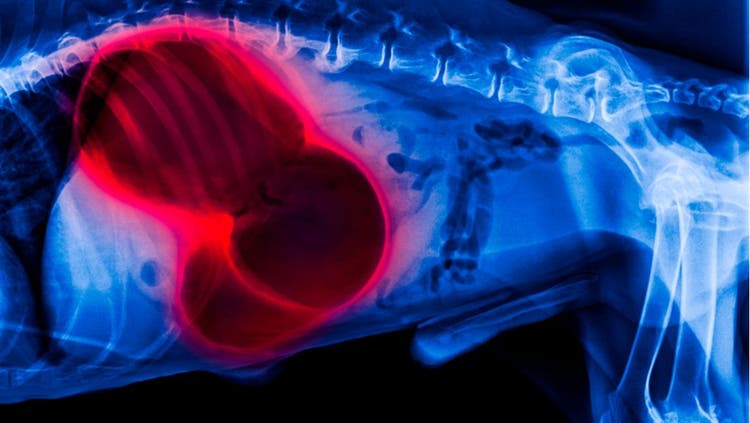

- The diagnosis can usually be made based on radiographs, history, and physical examination.

- Physical exam findings may include an abnormal heart rhythm, pale gums, high heart rate, poor pulses, severe abdominal discomfort, increased respiratory rate and effort, collapse, or a comatose mentation.

- Radiographs of your dog’s abdomen lying on the right side (right lateral abdomen) is the view of choice for differentiating and diagnosing either a simple bloat or GDV.

- Bloodwork will include a complete blood count, blood biochemistry, and emergency blood gas analysis. Repeat biochemistries will be recommended if initial tests are abnormal.

- An electrocardiogram (EKG) is often needed to monitor for cardiac arrhythmias.

- Blood lactate may be a prognostic indicator as a higher level indicates a worse prognosis. It is believed that lactate levels greater than 6 mmol/L are associated with an increased mortality.

- Coagulation studies may be done to identify disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, a syndrome that can cause blood clotting problems.

Treatment of Gastric Dilatation Volvulus (GDV) in Dogs

- Initial treatment of GDV will include emergency treatment for shock with intravenous fluids, drug therapy, and decompression of the stomach.

- Surgery is the definitive treatment for GDV. Emergency surgery is the recommended treatment to untwist and stabilize the stomach. Surgery should not be delayed unnecessarily. If the spleen is badly damaged, it may need to be removed (splenectomy). If the stomach lining is not viable, then a portion of the stomach may also need to be removed (gastrectomy).

- To prevent recurrence, a gastropexy is performed where the stomach must be attached to the abdominal wall.

- Monitoring for 2 to 4 days that includes observation for arrhythmias using an electrocardiogram.

- Post-operative pain management with opioids is most common.

- Fluid therapy to ensure that an adequate blood potassium level is maintained.

Surgery for bloat can cost anywhere from $1,500 to $7,500, based on your pet’s size and breed, as well as your geographic location. If you’re concerned about upfront costs related to veterinary surgery for bloat (as well as a variety of other conditions), The CareCredit credit card can help you manage expenses and pay over time with flexible financing **. See if you prequalify online today* without impacting your credit score and don’t let the unexpected get the best of you!

Prognosis for Dogs with Gastric Dilatation Volvulus (GDV)

The first four days postoperatively is the most critical time frame for dogs suffering from GDV. The mortality rate is approximately 15% for dogs treated surgically. The mortality rate is more than 30% for dogs treated surgically for which gastric resection is required. With surgery, recurrence rates are less than 10%.

Home Care and Prevention of Bloat in Dogs

- If you observe signs of GDV at home, see your veterinarian immediately. There is no recommended home therapy for GDV.

- Feed small frequent meals and limit water intake for one hour after eating and avoid large volumes of water intake.

- Limit exercise after eating.

- Do not feed from elevated feeding bowls.

- Avoid stress.

- For dogs that are at high risk for GDV, a prophylactic gastropexy is often performed when they are a puppy, this can be discussed with your veterinarian.

*Subject to credit approval. See carecredit.com for details.

** Minimum monthly payments required.

CareCredit is a credit product offered by Synchrony Bank. PetPlace does not own, administer or make decisions regarding CareCredit. An affiliate of Synchrony Bank holds a minority equity interest in an affiliate of PetPlace.